A son of Texas, Ron Woodroof (Matthew McConaughey) is an electrician and rodeo cowboy. In 1985, he is well into an unexamined existence with a devil-may-care lifestyle. Suddenly, Ron is blindsided by being diagnosed as H.I.V.-positive and given 30 days to live. Yet he will not, and does not, accept a death sentence.

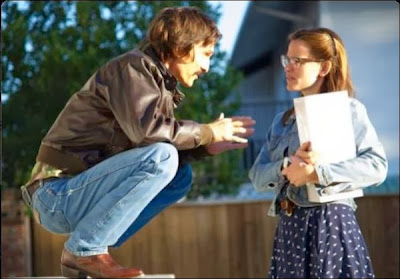

His crash course of research reveals a lack of approved treatments and medications in the U.S., so Ron crosses the border into Mexico. There, he learns about alternative treatments and begins smuggling them into the U.S., challenging the medical and scientific community including his concerned physician, Dr. Eve Saks (Jennifer Garner).

An outsider to the gay community, Ron finds an unlikely ally in fellow AIDS patient Rayon (Jared Leto), a transsexual who shares Ron's lust for life. Rayon also shares Ron's entrepreneurial spirit: seeking to avoid government sanctions against selling non-approved medicines and supplements, they establish a "buyers club," where H.I.V.-positive people pay monthly dues for access to the newly acquired supplies. Deep in the heart of Texas, Ron's pioneering underground collective beats loud and strong. With a growing community of friends and clients, Ron fights for dignity, education, and acceptance. In the years following his diagnosis, the embattled Lone Star loner lives life to the fullest like never before.

Making a feature film on a 25-day shooting schedule made for an adjustment for all concerned. But for Dallas Buyers Club director Jean-Marc Vallee, it was also an opportunity to maximize every minute of the shoot in a way that no one could have anticipated: he would simply not artificially light anything.

Vallee had only recently reduced his reliance on artificial lighting for Cafe de Flore, which was shot entirely handheld on and with the RED digital camera. During production, half of the shots were lit with artificial light and the other half were not. The director remarks, "I now had a perfect opportunity to try to shoot an entire movie without artificial lights, using the Alexa digital camera. Like the RED, the Alexa offers a broad spectrum of colors and shadows in even the darkest natural lighting conditions."

"I felt that the approach was right for this project. The look and feel became that we were capturing reality; even though Dallas Buyers Club is not a documentary in content or structure, it could have that subtle quality. We shot the movie 100% handheld with two lenses, a 35-millimeter and a 50-millimeter. These get close to the actors and don't skew the images. [Director of Photography] Yves Belanger adjusted for every shot at 400 or 1600 ASA [camera speed], displaying different color balance."

Emmy Award-nominated production designer John Paino did bring in practical, working lamps that were germane to scenes and added light. Even so, states Vallee, "We generally made do with existing light. I must credit John's hard-working design team and my and Yves' Montreal compatriots like first assistant cameraman Nicolas Marion, and script supervisor Mona Medawar. They helped me be able to film without set shots -- and keep track of it all!"

Belanger reveals, "We had our core camera crew, but this was still my first American movie. At the same time, Jean-Marc and I have known and worked with each other for two decades, but this was our first feature together."

Vallee enthuses, "Yves is a cinema encyclopedia. He also has a way of feeling the shots and the light so we will sense how to proceed creatively."

The cinematographer notes, "For commercials shoots that Jean-Marc and I have collaborated on, we developed a style base of working with existing, available light and playing with it. So Dallas Buyers Club starts from that base, and further we did not use any camera tripods or dollies to make this movie."

Producer Rachel Winter muses, "When Robbie Brenner and I heard that Jean-Marc was only using practical lighting in this movie our first reaction was, 'What...?' Well, it looks phenomenal and adds to the storytelling. It also yields a different rhythm. We've gotten something very special under his direction and Yves' lensing."

The director felt that he could make the movie in this new style because of the solid foundation of cast, crew, and detail. Robin Mathews and her make-up team, Adruitha Lee and her hair unit, and costume designers Kurt and Bart and their department worked closely together. Advancing beyond studying the documentary How to Survive a Plague, everything from photographs to club flyers to documentation of activists' sit-ins was accessed. The gay publication The Dallas Voice proved to be a particularly valuable resource.

Jared Leto states, "Our crew -- wardrobe, hair, make-up -- did really tremendous work and helped us bring these characters to life."

The costume designers reveal, "We liked the way the script portrayed Rayon as someone who was shaped by different influences. While working on how Jared would represent her we kept thinking about people from our past, people who were transitioning [gender] like Rayon. Some of our friends had been photographed by Nan Goldin, and we looked over her work with Jared.

"Since the character has great taste but a limited budget, we went to some vintage places for her wardrobe. We would collaborate with Jared every day because we felt that Rayon would have found something here and there -- and always end up looking good."

Winter reveals, "A key reference point for Rayon's look was the 1970s glam rock star Marc Bolan. What Kurt and Bart worked out with Jared was gorgeous; on the set, women would say, 'Do not stand next to me, Rayon, it's not fair.'"

Kurt and Bart also worked to accentuate the weight fluctuations of the characters by changing the sizes and dimensions of clothing. Kurt and Bart reveal, "Earlier in the story, when Ron is deathly ill and doesn't know why, we put Matthew in bigger clothes; even his belt is a little bigger. It made him look as if his clothes don't fit him any more. We did have multiples of some of key clothes, including for later in the story, when he has stayed alive and even gained some weight back."

In working to accentuate stages of characters' being healthier or sicker, Mathews notes that "coordinating these looks with Adruitha, and with Kurt and Bart, was a challenge. People will think, 'Oh, the movie was shot at two different times for Matthew to lose and gain weight,' because that's the way other films have been made. This was not the case."

Prior to production, Kurt and Bart visited "the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center in New York City and the New York Public Library, both of which had amazing archives on the look of the period -- including all the political-statement buttons that people wore."

The costume designers, having grown up in Denver and Colorado, voice "a huge appreciation for the West, and the cowboys that still exist there today. In terms of menswear, the classics are still around. Cowboy-cut jeans haven't changed much in decades. For Ron, it was tapered shirts with long tails, long sleeves, and snap fronts. Although the story takes place in the 1980s and beyond, Ron has probably gotten his clothes at a thrift store -- so some of the shirts Matthew wears early on are more 1970s ones, with bigger collars.

"We also enjoyed outfitting Ron with 1980s shirts, a new hat and some snakeskin boots when he's got a little money. Texas was being glamorized in pop culture by that point, what with Dallas and Urban Cowboy, so we had a lot to work with visually. Richard Avedon's portrait photos in In the American West also helped us get into Ron's world."

The costume department scoured thrift stores for polyester suits, big belt buckles, waist-high jeans, and shoulder pads, among other '80s fashion finds.

Jennifer Garner muses, "Wearing those jeans way up on my waist -- it's funny how much clothes can take you back to a certain time. While playing Eve, I found myself wearing the kind of clothing that I can remember on my mother.

"I picked up the copy of Time that was brought in for a scene. Well, my family has gotten Time my whole life and I remembered reading that issue. The props, like the clothes and the hair, took you back and put you right there."

While the '80s setting and research might have been expected to occasion a trove of favorite songs from the era, and Vallee has made period accompaniment a key component in his movies, in Dallas Buyers Club there is no composed score and only minimal ambient or source music; the drama of Ron's journey has its own rhythm.

Given the fleet shooting style and schedule, locations' interiors and exteriors had to be prepped for the director and actors to be free to move almost anywhere; every place, everything, and everyone had to be ready for anything when the time to start filming was at hand. Interior sets were fully dressed and "hot." This was unlike the traditional method of staging where, after an establishing or master shot, specific angles and camera moves are cycled through with lights, equipment, and crew waiting just behind or beside what the camera sees. Without the usual physical boundaries in the form of equipment carts and lighting and grip stands, there were less people able to be on the set; on Dallas Buyers Club, crew, equipment, and anything else that did not belong in the shot were outside, around a corner, or in another room nearby.

Vallee remembers, "There would often be nobody in a room but the cameraman, the sound man, the actors, and me. I completely trusted the emotions on the page and the actors in front of the camera."

With the time that would usually be spent on lighting set-ups saved and with make-up and wardrobe changes minimized, the prep, pace, and working dynamic for every department and crew member was completely changed; it was more similar to staging a theatrical play performance, with actors moving within a dressed arena, than to a traditional film shoot. But unlike the few hours of active duty for a play performance, the crew on Dallas Buyers Club had to keep a running pace for 12-18 hours daily.

"It was constant running around," comment Kurt and Bart. "There was none of the usual downtime or breathing room between scenes, so several things had to be going on simultaneously all the time -- taking care of the present scene, readying for the next, and prepping for the ones later. Pages and pages of dialogue and scenes were being shot every day. It felt like a 40-day shoot done in 25 days."

Overall, the actors and crew found the pace to be exhilarating. McConaughey remembers, "The only days where we'd lose time came when Jared and I were both working; we'd both have a lot of make-up and would have to share Robin [Mathews]."

Mathews adds, "We'd hear 'Ready to shoot in five' while in the middle of huge make-up changes -- going back-and-forth from sick to healthy. But it was an amazing experience."

Garner reveals, "This movie was the first project on which I'd ever done scenes where there was no lighting. I have to say I loved it, how we were on our toes and could shoot six, seven, eight scenes a day. It was incredible -- and gave us plenty of acting time. You don't feel shortchanged; you never lose momentum, you're always moving and thinking. You stay charged -- since you're not sitting around between takes -- and the whole team is in it together, which is great."

Vallee looked to inspiration in the trail blazed by an independent filmmaker through the 1960s and 1970s. He comments, "I was hoping to attain something in line with the films that John Cassavetes made, being about the moments of true intimacy. He just went everywhere with his cameraman following the actors, and it was happening in front of you. Even if something went out of focus, it would make the cut."

The cut for Dallas Buyers Club was made by the director with Martin Pensa, the film editor. In expanding the working relationship established on Cafe de Flore to being co-editors on the new movie, Pensa says, "I feel blessed to be among Jean-Marc's close collaborators; he keeps on pushing the limits and surpassing himself, and I learn so much from working with him. I'm very proud of what we achieved on this film."

In taking cues from Cassavetes' directorial style, Vallee encouraged the actors to roam with a freedom and spontaneity rarely found in more traditionally staged, framed, and choreographed scenes. He remarks, "It deepened the intimacy with the actors, and we were also ready to go this way or that with the camera. It allowed us to do a 360-degree shot, which is really being in the moment."

Garner praises "Jean-Marc's sensibility, how he set up an environment so that things can happen on the fly. Someone would have an idea, we'd shoot in one direction -- and then turn back around after discovering something else, to capture that."

McConaughey elaborates, "He won't stop the camera; he'll run into the other room and say, 'Please back up and re-enter [the room].' 'Okay!'"

Leto enthuses, "I wish every actor could have this experience with the camera still rolling because it's so alive and you're completely un-self-conscious."

"It's the way I'd love to do it every time," states McConaughey. "You have your script [memorization] down [pat], and it's camera-rolling-and-go. Show up each day and get to the work. You're behaving more than you're acting. I felt it was a new way of filmmaking.

"These 13-14-hour filming days we did? That's a fatigue I enjoy feeling; you're in construction the whole day, building something together."

Michael O'Neill adds, "We felt like renegades; we'd move and move fast. No one was off in a trailer. You're just in it, and that was fun. Jean-Marc would be racing around a courtroom set-up with a camera on his shoulder, enthusiastically speaking French."

Despite the brisk pace, nothing in the frame escaped the director's eye. McConaughey remarks, "I was impressed with how Jean-Marc would set up shots while working out what was right for the character and the actor. He has confidence, and also no ego about who has the best idea -- he'll say, 'That isn't what I had in my head but I'm hearing it now; I get it and I like it.'"

Garner adds, "He's plain-talking but he's also kind. I think that's a combination of strength for a director."

As a filmmaker himself, Leto feels that Vallee's "way of filming is very conducive to getting good performances out of people because it was so fluid. He is an actor's director. "Jean-Marc can be very controlling, which you have to be when you're directing a movie. But he is so open; he likes to keep things playful and experimental, so everyone can have an opportunity to collaborate and be creative."

The actor concludes, "He knows what he wants, but if he doesn't then he will fight to get it."

As Ron Woodroof learned, knowing what you want is the first step to getting it. He knew he wanted to live, and achieved that goal to an extent he couldn't have imagined.

In 1992, screenwriter Craig Borten asked him how he would feel about his story becoming a movie one day. Borten reports, "Ron said, 'Man, I'd really like to have a film. I'd like people to have this information and I'd like people to be educated on what I had to learn by the seat of my pants about government, pharmaceutical agencies, AIDS. I'd like to think it all meant something in the end.'"

No comments:

Post a Comment